RRR – Books: Asia's New Geopolitics: Essays on Reshaping the Indo-Pacific

The archetypal of great powers which lead to an irreversible path between the amelioration of "rapprochement" or the acrimonious "duel of fates".

Author : Michael R. Auslin

Publisher : Hoover Institution Press

Page count : 263

Publication date : April 29, 2020

Currently, we live in a world where peace is such a strong word, so strong that we tend to take it for granted. We give such importance to the word peace, but we don’t tend to notice it when it occurs, sometimes it takes reminding ourselves of how terrible war once was to see the peace that has been growing around us. Alas, this trend proven to be ephemeral, and personally, I believe that as long as human exists, conflict will always entail whether we like it or not. Nevertheless, I’m not a proponent of an immediate hawkish approach, rather toward calibrated engagement but that doesn’t necessarily make me a pacifist either. Armed conflict between nations is a nightmare to every single one of us, and it is exactly why, brute force should become a tool that reserved as the very last resort. Thus, every problem doesn’t have to be conceived as a nail that waiting to be hammered.

As per usual, of course my personal bias and naïveté might affect the statement that I just made and also might changes as time moves forward. However, sooner or later, there will be a point where war is inexorable as portrayed before in the history of our existence in this world. Before we embark on it, we must be very clear, that life for those who believe in liberty would not be worth living under circumstances where domination achieved by fear of force. Hence why it’s a privileged to be able to live through peace time and learn from the past on what we can truly be capable of when it comes down to conflict amongst nations. Thus, those lessons showed us on the importance to forestall the possibility of an all-out wars as long as possible, particularly in this nuclear-age time.

Unfortunately, just recently, peace itself broke out. Although not in a scale of “World Wars”, yet perhaps the largest in Europe since WW II. Moreover, it’s a shocker that it happened on top of already a cataclysmic event such as pandemic of SARS-CoV-2. Nonetheless, it’s interesting if we use World Wars as the pinpoint. John Gaddis who has been hailed as the “Dean of Cold War Historians” coined the terms of “The Long Peace” as to identify the absence of open-conflict between nuclear power during the Cold War—extremely close during the Cuban Missile crisis in 1962—even up until now. It is true that wars have occurred since WW II whether it’s fought between non-state actors, civil wars, or interstate wars. However, one can’t deny that the largest economies in the world have not battled each other since WW II. Big countries have fought smaller countries (i.e., US versus Iraq or Afghanistan) but big countries have not fought other big countries openly in a Total War scenario and such period of peace between the so-called Great Powers hasn’t been seen since the Roman Empire.

Despite the existence of Long Peace, there’s a concern lingering around which called the “Thucydides trap” where it refers to a situation where a declining power might be collided with the rising power. However, such collision can still be avoided if it handled properly by both sides but oftentimes this terms also portrayed the bleak of an inevitable conflict. One example that often cited the most is when this happened between the rising power of Athens and the declining power of Sparta during the antiquity. As a result, their struggle for power led to the path of inevitable conflict. In addition, both had direct border with each other’s, their proximity should never be underestimated as one of the main factors of their possibility to opted for conflict. Nowadays, similar situation might happen between the declining power of United States vis-à-vis the rising power of China. Therefore, through this book, Michael R. Auslin elucidate the possibility of such collision. While US and China are not directly bordering each other’s, in terms of geopolitics, it is safe to assume that they are at each other’s spheres of influence. Since the end of WW II, US has maintained the dominant position in the Pacific region, such hegemonic position is now challenged by the rising power of China. Thus, can US and China avoid the so-called Thucydidean scenario?

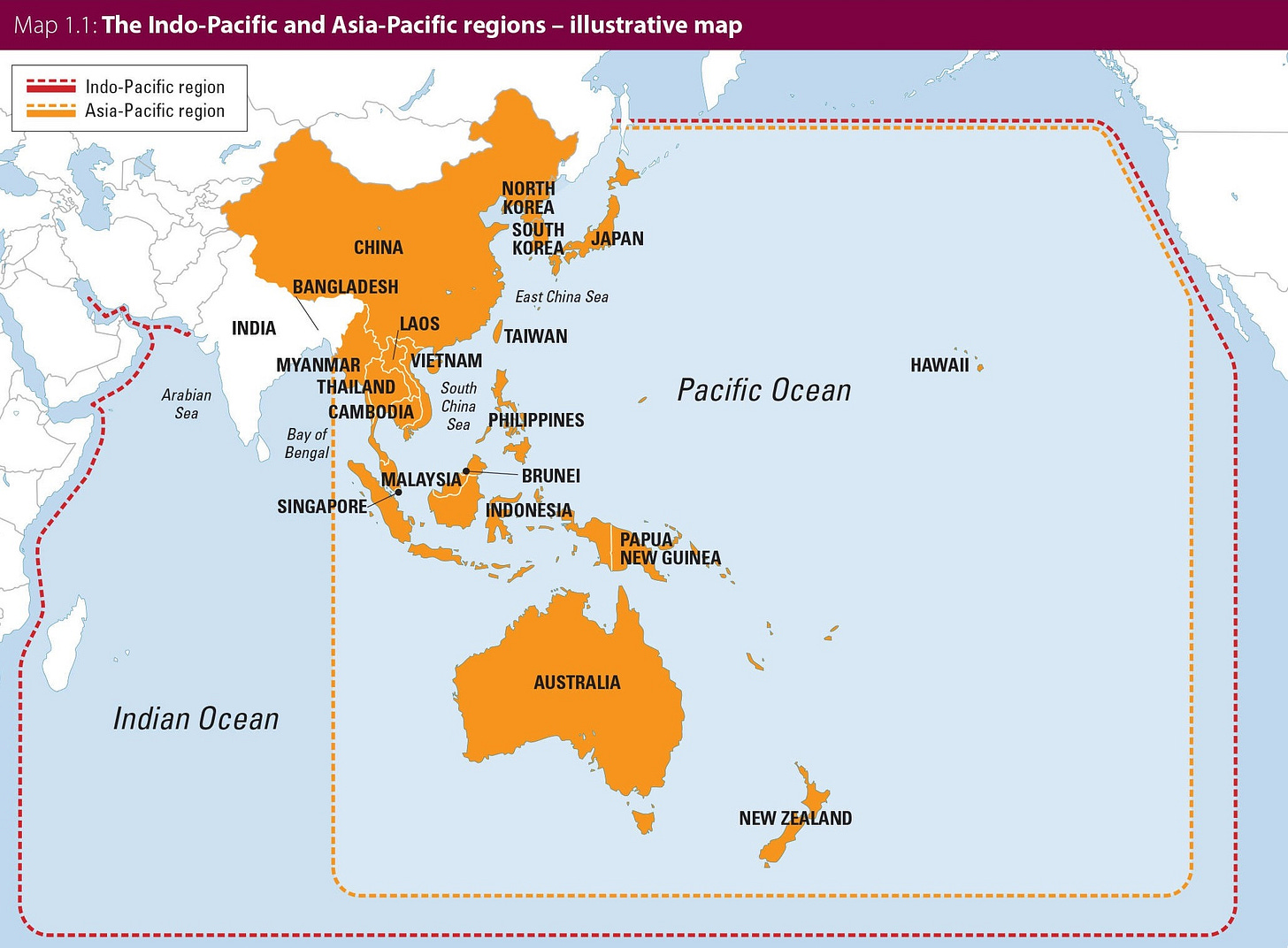

As the title of the book said, Auslin’s area of interest that become the main foci of the book is on Indo-Pacific. Thereby, Auslin raised his concern on some of the key waterways like the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea, and the South China Sea. He analyzes the situation in the aforementioned waterways from the perspective of US strategy of “free and open” within Indo-Pacific. Nevertheless, Auslin didn’t use a linear path to elucidate the entirety of the book, hence why not all chapter are directly correlated or viewed from US point of view. I supposed it’s a better way to create more nuanced and balanced book. Furthermore, since Auslin himself is a trained historian, every chapter begin with a historical aspect which is noteworthy, since it’s imperative to understand the ebb and flow of countries that exist in Indo-Pacific.

The book gives a contribution to the field of International Relations by providing a clear insight on the dynamics of Indo-Pacific region. Moreover, Auslin chose some countries to be further examined as a separate chapter, inter alia Japan, DPRK (North Korea), China, and India. All countries elucidated not just from their domestic situation but also its nexus with the region of Indo-Pacific which prompt its readers to understand the way of thinking in each respective country. The importance of Auslin’s book dovetail with the current state of the affairs and in particular DPRK’s recent missile test and continued hostile relations between China and Japan but also India. The whole narratives provided in a less hawkish but more emphasized on strategic thinking that might not show or rarely shown from the mainstream media. On top of that, Auslin crafted and backed up his critics or arguments from a first principle standpoint and reason up from there while concurrently laying the groundwork from historic events that can be used as a delineation to propose his own view.

The most riveting part of the book is Auslin’s apotheosis which titled “The Sino-American Littoral War of 2025: A Future History.” It’s the most interesting part of the book, notwithstanding that it’s just a fiction but it still based on historical accident that exist between US and China. The delineation on how the conflict emerged and the elucidation on how the US allies in Indo-Pacific weigh in on their own national protection vis-à-vis all in to combat mode alongside US forces, were both well written and well structured. The depiction on the diplomatic tension that gradually ramp up, the “fog of war” after the first contact broke out between PLA Navy and US Navy, and the decision-making process to either escalate or de-escalate the conflict, all properly described in a cascading way. Interestingly enough, Austin chose Gavin Newsom (current Governor of California, as of this writing) as the US President in his fictional future war implying for a future Democrats administration.

In addition, Auslin also provide the conclusion of the conflict not only by showing the territorial gain and lost in the first and second island chains, encompassing Yellow, East China, and South China Seas but also the important lesson that being learnt primarily from the US side since in this wargame Auslin depict China as the winner and what it means to the geopolitical situation in Indo-Pacific. Each battle explained in a detailed manner, whether it’s in the Taiwan Strait, Senkaku Island, and the others. While in terms of technicality, it also includes the usage of A2/AD—anti-access, area-denial which include modern combat warfare such as anti-ship ballistic missiles, attack submarines, stealth fighters, swarming missile boats, and the like—capabilities from both forces of China and US. This scenario is not an all-out nuclear Total War that ruined the entire humanity, it emphasized in the small accident that turns into a tit-for-tat strategy but only in a specific and focused battle space.

Some may argue that Auslin might overestimate the strategic calculus of Chinese capabilities and portend this sense of threat inflation, which is also a possibility. However, despite the result, Chinese air forces were actually bested by their US opponents and lost their air cover which quickly backed up by their land-based missiles such as DF-21D ASBMs since the battle space is closer to China’s mainland. Albeit that the two countries came into armed conflict accidentally in this wargame, years of deteriorating relations can be constituted as a precondition to war since suspicion grew in each country about the other. The fact that two eyed each other as the major threat each faced, might create a fait accompli that an accumulated sense of distrust and uncertainties will eventually spiral into an uncontrollable conflict. To put it lightly, it’s like a frog boiling in a pot, the frog didn’t realize that as the temperature slowly increases one degree at a time it means one degree closer to death. As a consequence, it brings us back to the concept of Thucydides trap that’s looming around this whole time.

Nevertheless, concurrently, neither US nor China was totally sure on how to engage in this hostile environment where both have an antithetical strategic interest in the region. US want to maintain their “Free and Open” Indo-Pacific while China thinks that this is an opportunity to catch US off-guard because such opportunity might not happen again in decades, after all US forces were stretched too thin anyway, to fight effectively in the South China Sea. But it’s one thing to decide what a strategic interest will be and yet it’s another different thing when it comes to how to achieve those interests. Thus, this creates a confusion on how to respond, to what point a country should escalate to a full nuclear warfare, so on and so forth. This is where the factor of fog of war comes in and as a result both countries showed restraint during combat operations even after physical contact from both forces. The aftermath of the aforementioned clash is somewhat intriguing for me since I believe that this wargame is perhaps the closest scenario to what might happened in reality which start from small accident and escalate further but still in a confined battlefield.

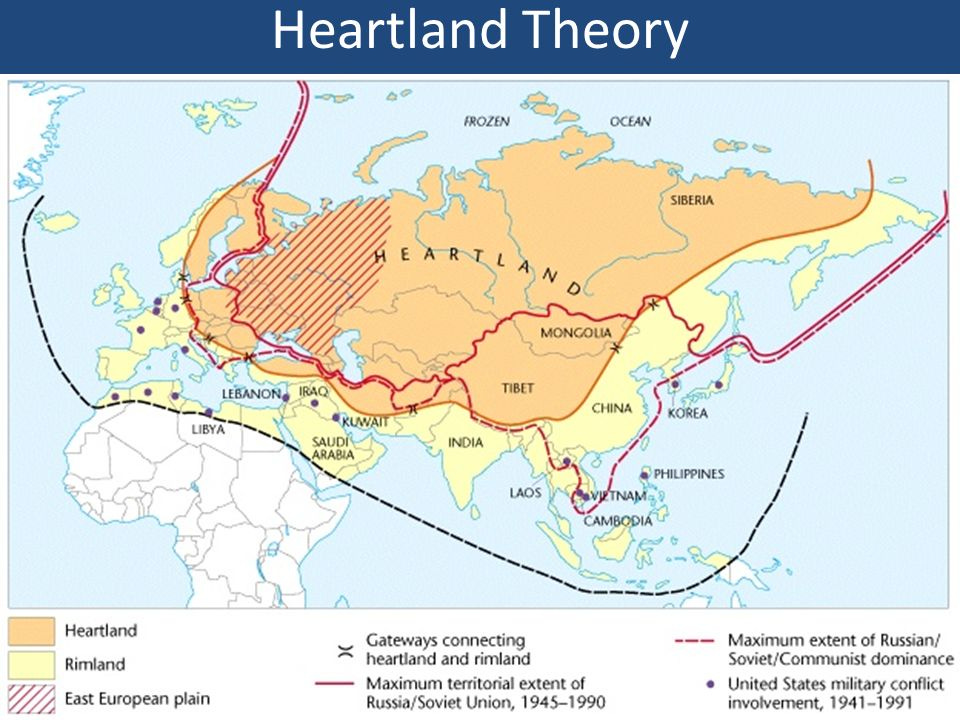

In the book, Auslin argued that the concept of “Indo-Pacific” is too vast of a battlefield. Therefore, Auslin opted to revives the concept of “Asiatic Mediterranean” instead. This concept delineates that if the Eurasian landmass was the “heartland” of geopolitics, then the “rimlands” at either end of it were the likely battlegrounds for its control. Originally, the concept emerged in an article titled “The Geographic Pivot of History” in 1904 by Halford Mackinder in which his main focus was on the land-based heartland. Four decades later, Yale geopolitical thinker Nicholas John Spykman modified such concept in his book “The Geography of the Peace” in 1944 which emphasized more on the importance of marginal or the littoral seas within the rimlands area. But the idea remains the same which is that whoever controls the heartland controls the world. Thus, in order to gain such power, one must go through the struggle of control in the rimlands which both guard and give access to the heartland. Thereby, it dovetails with Auslin’s concern in some of the key waterways in Indo-Pacific which include East and South China Sea, along with Yellow Sea. As the expanse of water between China and its neighbors—Korea, Japan, the Philippines, and Indonesia—this may well be regarded as Asia’s answer to the Mediterranean, but China increasingly treats all three seas as its own coastal waters.

As the general picture of Indo-Pacific, nowadays, it is perhaps the most diverse region on earth which comprises 36 countries that are continental, peninsular, and archipelagic, including tens of thousands of inhabited islands, and covers much of the Pacific and Indian Oceans. It contains over three billion people, more than half of global population, including world’s most populous nations like India, China, and Indonesia. In addition, it has the world’s largest democracy, India, and home of two of the world’s three largest Muslim majority population like India and Indonesia. Indo-Pacific is home to more than 40% of global economic output, including the leading economies of China, Japan, and South Korea. Furthermore, in terms of military, it contains some of the world’s largest and most developed military forces, including those of China, North Korea, South Korea, India, and Japan; as well as three declared nuclear powers (five, if the United States and Russia are included). Through its strategic waterways, such as the Malacca and Sunda Straits, transit some 70% of global trade and some 75,000 ships annually, linking Asia with the Middle East and Europe.

While the book provided the suggestion for US strategy in Indo-Pacific and all the necessary measures to take, Auslin argued that:

“America has lost a conscious understanding of the strategic importance of the inner seas and skies, at a moment when it faces the greatest challenge to its control of them since 1945.… China is contesting control not of the high seas… but of the marginal seas and skies of Asia, even while the United States remains dominant on the high seas of the Pacific.”

Later on, such argument will become the basis of Auslin’s apogee hence why in the wargame Auslin showcased that China is the winner notwithstanding US gain superiority in the air. That scenario reiterated the importance to not underestimated China’s willingness to use brute force as its means to gain control in the rimlands. Despite fighting brutal and domestically divisive wars in Korea and Vietnam, the United States was never forced to defend its position in Asia the way it was in Europe. In the case of China, Washington confronts the difficulty of dealing with a “near-peer” competitor whose goals are increasingly antithetical to its own.

Since 1950s, United States raison d'être is to maintain their dominance of Asia’s Mediterranean by establishing a close rapport with its five main Allies using bilateral treaties. These main Allies which include Australia (1951), Philippines (1951), South Korea (1953), Thailand (1954), and Japan (1960) are the key to assuage the possibility of China’s more aggressive action towards its neighbors. As for the Chinese side, it’s a sine qua non for them to gain control within the “first island chain” which extends from the Kamchatka Peninsula to the Malay Peninsula and encompasses the Kuril Islands, Japan, the Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, Northern Philippines, and Borneo. Conversely for Taiwan, they need to counter China’s influence and safeguard its own democracy by maintaining their relationship with US to preserve the Taiwan Relations Act (1979) which states that US will…

“…consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the US.”

“…make available to Taiwan such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability.”

The only direct assault that threaten US strategic interest to keep Pacific “free and open” is when the Japanese attacks throughout Asia on December 1941 and became the hegemonic military power in the region. The timing of Japanese was in conjunction with the threat posed by Nazi in Europe and together, they generated a serious attempt of strategic planning to undermine US global interests. One thing to keep in mind is that US’ unique geographical advantage of being protected by two great oceans would be irrelevant if Europe and Asia were both dominated by their adversaries which isolating US from global trade route and threatening its national security. If we go back to Spykman, to him continental defense (what he called “quarter-sphere” defense) was unviable without full hemispheric defense, including South America; that, in turn, could not be ensured without a favorable balance of power in both Europe and Asia in the Eastern Hemisphere. Thus, American forces had to be present in those far-flung regions, which became part of the argument for near-permanent forward basing of US troops in both Europe and Asia after 1945.

Geographically speaking, location of the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea, and the South China Sea are amongst the most vital waterways that connect the Asiatic Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean which one-third of global trade passes, in the form of over seventy thousand ships per year. Economically, US trade in goods with Asia totals nearly $1.5 trillion dollars, nearly double that with Europe. While the importance of this waterways is crystal clear, the challenge that posed by China toward governments that exist in the littoral of the Asiatic Mediterranean such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, and others are gradually increasing over time. In order for China to gain its desired result in the geopolitical chess, they understand that control of the Asiatic Mediterranean means control of Asia.

Therefore, the aforementioned governments in the littoral of Asiatic Mediterranean as well as those in the Indo-Pacific’s rimlands such as Philippines, Indonesia, and Australia—which are uniquely composed of continental, peninsular, and archipelagic landforms—that the global trading network depends on are now faced with perilous situation where its maritime and aerospace freedom could be threatened and thus disrupt its productive and trading capacities. An Asiatic Mediterranean dominated by China would severely limit America’s strategic maneuverability, and potentially threaten its economic well-being. Thereby, Auslin believed that:

“China has every right to operate in international waters and protect its own national interests, but not at the expense of regional stability. The United States cannot intervene in every dispute between Beijing and its neighbors, but China equally cannot be allowed to unilaterally set maritime or aerospace rules of conduct or alter national boundaries, whether through intimidation or force. Rather than containing China at every turn, constraining its assertive and aggressive behavior, when necessary, should be America’s goal.”

The US strategy within Pacific itself can be traced back until 1860s during the President Lincoln’s administration. The argument at that time was, the domination of global commerce was America’s destiny, and that the Pacific would serve as a great highway to the riches of Asian markets. From this point onwards, US forces start to annexed Hawaii, Philippines, Guam, and Samoa. America overturned nearly a century of tradition and became one of the leading colonial powers in the Pacific. Auslin also broached the shift of US behavior in their engagement with Asia-Pacific particularly from Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” until the new term of “Indo-Pacific” being used under Trump administration. Despite the rhetoric that underlines the importance of Indo-Pacific from US government, it resulted in an ambivalent feeling for Asian countries. The existence of “parachute diplomacy”—where US officials fly into the region, convey their reassuring speeches of America’s continuing commitment, and then just simply fly out—might be the cause of this whimsical impression.

Even during Trump administration, US shake their own core alliance in the region by pertains the economic imbalance and suggest both Japan and ROK should be paying more to offset the costs of basing US forces in their countries while concurrently, inculcating the idea that US might consider walking away from the alliances if Tokyo and Seoul did not contribute more funds. Afterwards, what’s even more baffling is that Trump suggested that he might encourage both countries to develop their own nuclear capabilities in response to North Korea. This threatened to undermine the long-standing US nuclear guarantee of so-called extended deterrence, by which Washington promised to defend both Japan and South Korea from nuclear attack in exchange for both countries forgoing an indigenous nuclear deterrent. Meanwhile during Obama’s pivot to Asia, Beijing was ramped up their military presence in the South China Sea. But Washington seems outmaneuvered in the South China Sea hence why Obama’s pivot increasingly seen as mainly rhetoric since Beijing was not deterred from their militarization within artificial islands of South China Sea.

Ultimately, not only this book has been influential for those who are interested in contemporary geopolitics, but also provided a different lens to apprehend the importance of Indo-Pacific by using Spykman’s theory of Asia Mediterranean, despite that it’s an old theory and didn’t account for the massive improvement in warfare technology like hypersonic missile and cyber capabilities, at least it brings the reader’s attention to the concept of Rimlands and its nexus with hitherto geopolitical situation. On top of that, lots of details and indices that the readers will find fascinating throughout reading this book, in particular about the circumstances in both Japan and India, who domestically fought a hard battle between tradition and modernity. As of this writing, it will be interesting to see the current US administration to assuage the situation in South China Sea and stem China’s rising influence within Indo-Pacific, economically, culturally, and militarily.

Michael R. Auslin is the inaugural Payson J. Treat Distinguished Research Fellow in Contemporary Asia at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. He is also a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and a fellow of the Royal Historical Society.